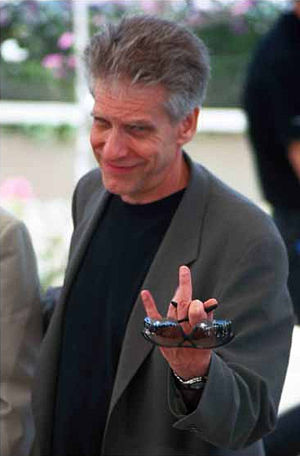

David Cronenberg is smarter than me. Sure, that's true of a lot of people, but he's

exponentially smarter than me. That's why I have such a healthy case of man love for him. He makes movies that are so thematically layered, rich in subtext, and challenging to the viewer that I return to them again and again. I tend to key in on different particulars each time I revisit a Cronenberg movie, making his catalog almost infinitely rewatchable.

Don't worry, though. You won't feel as though you're being talked down to. Watching a Cronenberg movie is more like being drawn into a dialog with an endlessly fascinating guest at a cocktail party - a fascinating guest with loads of very peculiar preoccupations involving human sexuality, disease, technology, malignancy, psychology, fetishism, media consumption, and evolution by way of mutation.

What follows is a list of the very best of David Cronenberg's contributions to the genre. I've listed the titles chronologically so as not to imply any sort of arbitrary ranking. If you're new to his work, every title listed is worthy of your attention. If you're already a fan, go ahead and treat yourself to a second or third viewing of your favorites. All hail the

King of Venereal Horror, and Long Live the New Flesh!

_______________________________________________________________________

Shivers (1975)

aka They Came From Within

In

Shivers, parasites genetically engineered to be organ transplants are unleashed within the isolated gated community of Starliner Towers. Those hosting the parasites display violently hedonistic behavior, and the outbreak propagates itself in a manner akin to the spread of a social disease. While understandably less polished than his later work,

Shivers finds Cronenberg beginning to explore his career spanning fascination with body horror.

There's a strong allegorical component concerning the violent implosion of an isolated society, as well. The depiction of the community's final descent into anarchistic chaos and unfettered sexual abandon is chilling.

Shivers was partially financed by the taxpayer funded National Film Board of Canada, and Canadian journalist Robert Fulford attacked the movie in a national publication with an article titled "You Should Know How Bad This Movie Is, You Paid For It." Cronenberg was already courting controversy, a recurring motif throughout his career.

_______________________________________________________________________

Rabid (1977)

Rabid centers on the victim of a motorcycle accident (former porn star Marilyn Chambers) who's treated with an experimental skin grafting procedure that leaves her with a bloodsucking phallic mutation under her arm and an insatiable lust for blood. She flees the hospital where the procedure was performed, leaving a trail of violent, diseased victims in her wake. Her attacks soon lead to a city wide epidemic, and martial law is declared in an attempt to quell the outbreak.

Though

Rabid shares many thematic concerns with

Shivers (mutation, medical experimentation, societal collapse), it's a more technically proficient movie that maintains a more consistent feeling of dread than its predecessor.

Rabid plays out more like a traditional horror movie, albeit one that possesses a seething mass of that peculiar Cronenberg sensibility at its core. It's probably the least of the movies on this list, but it's an important step in Cronenberg's evolution from twisted b-movie maven to full-fledged auteur.

______________________________________________________________________

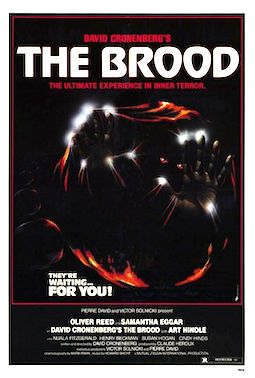

The Brood (1979)

Cronenberg wrote

The Brood after a difficult divorce and child custody battle, and when viewed in that light it's hard to miss what one assumes are autobiographical underpinnings present in the script. Cronenberg has acknowledged that the character of Nola Carveth (Samantha Eggar), the source of the movie's murderous brood of mutant offspring, possesses some of the characteristics of his ex-wife. Given that the brood seems to be the physical manifestation of Nola's barely suppressed rage, it's not a flattering portrayal. It's not much of a leap to read Nola's megalomaniacal psychologist Dr. Hal Raglan (Oliver Reed) as a fictionalized depiction of a manipulative lover, either.

The Brood's final moments, which seem to suggest that Nola's "real" child Candy has been so deeply traumatized by the events depicted that she's doomed to someday produce a rage-filled brood of her own, are as bleak and disturbing as any in Cronenberg's filmography. The implication that Candy's father Frank Carveth (Art Hindle) is unable despite his best efforts to prevent this outcome is heartbreaking.

Cronenberg's viewpoint can sometimes tend toward being off-puttingly clinical and detached. His obvious emotional involvement with the subject matter makes

The Brood one of his most personal movies, and not coincidentally, one of his best.

_______________________________________________________________________

Scanners (1981)

Though all of Cronenberg's films had been financially successful up to this point,

Scanners was his breakout movie. Scanners are individuals with a unique form of ESP that allows them to read the thoughts of others as well as to literally "blow minds."

Scanners is a parade of grotesqueries highlighted by an

exploding head that found permanent residence in the pop culture lexicon and finally put Cronenberg on the radar of a much wider cross-section of viewers.

Michael Ironside creates an indelible villain in the form of Darryl Revok, the most powerful of all scanners and leader of an underground group bent on exploiting the unique abilities of the scanners to ultimately achieve world domination. Unfortunately,

Scanners is undermined somewhat by weak performances elsewhere, particularly Stephen Lack's underwhelming performance as "good" scanner Cameron Vale.

In

Scanners, Cronenberg continues to explore his preoccupation with the violence both physical and psychological that human beings inflict upon one another. He also begins to examine more closely the vulnerability of our bodies to assaults from modes of attack neither previously imagined nor presently understood, a theme he develops with more poignancy and greater success in

The Fly several years later.

_______________________________________________________________________

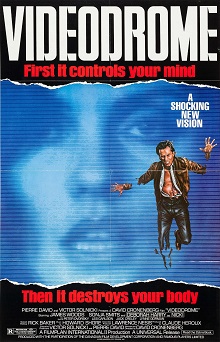

Videodrome (1983)

Though largely well reviewed at the time of its release,

Videodrome was a huge commercial disappointment. One can assume that it was simply ahead of its time, since its examination of how our collective perception of reality can be perverted by media imbued with the sometimes dangerous philosophy of its creators now seems disturbingly prescient. Though the technological specifics of how that dangerous content is disseminated (Beta videotapes, giant C-Band satellite dishes) may now seem anachronistic,

Videodrome's message has never seemed more timely.

The scene in which oily cable television programmer Max Renn (a never better James Woods) witnesses a roomful of homeless people in the "Cathode Ray Mission" each being encouraged to sit in front of his or her own personal television monitor for marathon sessions of t.v. viewing is chilling. Renn is told it's to help patch them back into "the world's mixing board." One cannot help but be struck by how much this bizarre tableau resembles a roomful of people choosing to ignore the others sitting in the same room with them while staring intently at the screens of their cellphones as they "socialize" via texting.

Videodrome is also one of Cronenberg's most visually audacious movies. It's filled to overflowing with upsettingly organic hallucinatory manifestations of technology - "breathing" televisions, diseased videotapes - created by FX pro Rick Baker, and the stark and garish sadomasochistic Videodrome transmissions themselves are no less unsettling. Regardless of what one makes of

Videodrome's frequently disjointed narrative, it's a movie rife with indelible images.

Videodrome is arguably Cronenberg's masterpiece. It's a movie with his unique visual aesthetic hardwired into a story chock so full of his thematic preoccupations that the narrative sometimes stumbles beneath the weight. It's essential viewing, but it probably

isn't the best point of entry for those unfamiliar with Cronenberg's work.

_______________________________________________________________________

The Fly (1986)

Eccentric scientist Seth Brundle (Jeff Goldblum) is doomed to slowly mutate into a hybrid of man and fly after a botched experiment in teleportation fuses his DNA with that of a common housefly. A remake of the hoary old 1958 chestnut of the same title,

The Fly is one of a small handful of examples from the horror genre that proves indisputably that a remake can be worthwhile, in this case even improving upon the original.

The Fly is probably Cronenberg's most accessible genre movie, and not surprisingly, it's also his most financially successful.

Cronenberg's metaphorical examination of the very real and devastating horror of helplessly watching someone you love fall prey to the ravages of disease is emotionally devastating. Jeff Goldblum delivers a spellbinding performance as the doomed Seth Brundle, much of it while wearing the brilliantly conceived full body makeup effects that earned creator Chris Walas an Academy Award.

As is often the case with Cronenberg's protagonists, Brundle is isolated in an insular world of his own obsessions. He's fascinated by the particulars of his metamorphosis, collecting the last vestiges of his humanity in a medicine cabinet - ears, teeth, fingernails - as they literally fall away from his body. Goldblum has always been an odd duck, and his physical tics and peculiar semantics suit the character of the dissociative scientist Seth Brundle so perfectly that one wonders where the actor ends and the performance begins.

Highlighted by flawless execution, strong performances, and impeccable craftsmanship,

The Fly is the culmination of Cronenberg's "body horror" phase as well as being an obvious high water mark in his filmography.

______________________________________________________________________

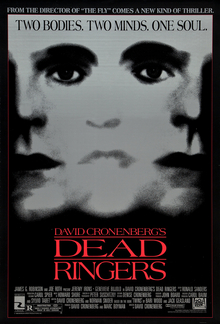

Dead Ringers (1988)

Cronenberg has always had a knack for pulling superlative, often surprising performances from his actors. In

Dead Ringers, Jeremy Irons plays identical twin brothers Elliot and Beverly Mantle, and he succeeds in creating two distinct and complex characterizations without lapsing into gross caricature to distinguish them. It's an amazing performance(s).

Elliot and Beverly are both gynecologists specializing in the treatment of women with fertility problems, ironic in that neither truly understands the figurative "inner workings" of females. Elliot is the more confident of the two, a Lothario who beds his conquests until he loses interest in them, at which point he passes them along to his more timid brother Beverly. Because they're unable to distinguish the two from one another, the women are unaware of this subterfuge and believe they're still with Elliot.

Ultimately, both brothers develop an attraction to actress Claire Niveau (Genevieve Bujold), at least in part because she possesses the physical anomaly of a trifurcate uterus. Beverly commissions the creation of "gynecological instruments for operating on mutated women," medical instruments that look like medieval torture devices. His implementation of the instruments ruins his career and leads inexorably toward an almost preordained endgame of dissolution and death wherein the only way out for the codependent brothers is together.

Though Cronenberg is still indulging his fascination with anomalies of the flesh, the primary focus of

Dead Ringers is more psychological in nature. Cronenberg's preoccupations mature, becoming less concerned with the malignancies that can destroy our flesh and more so with the malignancies that can destroy our very humanity. If

The Fly is Cronenberg's master's thesis on body horror, then

Dead Ringers is his first bold step toward a more profound and expansive examination of the human condition.

_______________________________________________________________________

Naked Lunch (1991)

The William S. Burroughs novel

Naked Lunch was long deemed unfilmable by most, so much so that Cronenberg knew attempting a straight adaptation would be folly. He instead chose to mix elements of the book - as well as elements of other Burroughs texts - with biographical information about the man himself. What he ended up with is a perverse and compelling cinematic singularity that imagines the world as experienced by junkie author and latent homosexual Bill Lee, the movie's Burroughs surrogate.

Lee (Peter Weller) and his wife Joan (Judy Davis) are both addicted to the bug powder Lee uses in his job as an exterminator, Cronenberg's way of sidestepping excessive narrative focus on Burroughs' real life drug problems while still allowing him to examine the nature of addiction. Lee shoots and kills Joan in a game of William Tell (a biographical element), and then things begin to get weird -

really weird, even by Cronenberg's standards.

Lee descends into a hallucinatory world called Interzone, a world at once both familiar and alien. Interzone is a world filled with talking, beetle-like typewriters, paranoid conspiracy theories, deviant sexuality, and Mugwumps spouting fluids from the tops of their heads. It's a world both fully imagined and specific in its details - a fascinating place to visit, but you wouldn't want to stay. Cronenberg

does weave a pitch black thread of humor throughout, though, an element it seems many of the movie's detractors fail to recognize.

Though often nearly impenetrable,

Naked Lunch is probably Cronenberg's most surreal and ambitious movie. It's a difficult movie to capsulize, and it's equally difficult to forget.

| _______________________________________________________________________ |

|

Crash (1996)

Cronenberg tackled difficult and provocative source material again with his adaptation of the 1973 novel Crash by J.G. Ballard, and the result was probably the most controversial and polarizing movie in his filmography. Earning an NC-17 rating at the time of its release, Crash tells the story of a group of people - most of whom are car crash victims - who take sexual pleasure from automobile accidents.

Television producer James Ballard (James Spader) is involved in a head-on collision that kills the other car's passenger. While recovering from his injuries he begins an extramarital affair with Dr. Helen Remington (Holly Hunter), the other car's driver and wife of the deceased passenger. Their affair is born of their shared experience of the accident and their subsequent sexual arousal based upon it. Ballard and Remington ultimately find themselves part of an underground sub-culture of car crash fetishists headed by cult leader Vaughn (Elias Koteas), who claims to be interested in "the reshaping of the human body by modern technology".

Cronenberg relates his narrative largely by the way of the numerous sex scenes throughout the movie, an unusual structure to utilize outside of the confines of pornography. Many of the film's detractors would argue that the structure is appropriate because Crash is, in fact, pornographic. In particular, much of the negative criticism leveled at Crash decries the close associations it makes between violence and sexuality. The movie itself seems to make no judgement, presenting its subject matter in a flat and voyeuristic fashion that invites examination rather than involvement.

On a purely personal note that I feel is somehow relevant, Crash just happens to be the movie I was watching when my ex-wife announced that she was leaving me. Given that much of the thrust of its narrative revolves around the examination of stagnant intimate relationships and the extremes to which its protagonists go to revitalize them, I've always felt like the universe was having a bit of fun at my expense with that less than subtle juxtaposition. It turns out that I could not possibly have felt more emotionally dead inside when viewing Crash for the first time, an apt state of mind in which to consider its message.

__________________________________________________________________________

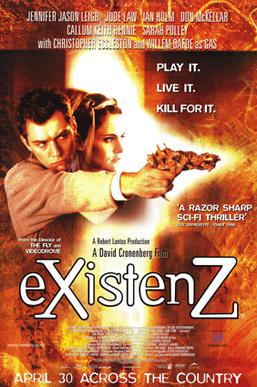

eXistenZ (1999)

Cronenberg at last lightens up bit for eXistenZ, the sci-fi leaning tale of Allegra Gellar (Jennifer Jason Leigh), the world's greatest game designer. Gellar has created a virtual reality game called eXistenZ, played with organic game pods that players jack into via umbilical cords plugged into "bio-ports" surgically installed in the players' spines. Gellar is shot in the shoulder during a focus group testing of the game by an assassin using an organic gun. The game pod containing the only copy of the new game is damaged during the assassination attempt, as well.

Gellar and security guard Ted Pikul (Jude Law) embark upon on an odyssey through the virtual world of eXistenZ to test the damaged game, and the real and virtual worlds become nearly indistinguishable. The pair struggles to keep themselves one step ahead of the forces intending to assassinate Gellar to halt the introduction of eXistenZ to the world. Everyone is a player, and no-one is really who they seem.

Cronenberg re-examines many of his recurring themes here, and it's easy enough to view eXistenZ as a less dour companion piece to Videodrome. Once again the lines blur between reality and fantasy, and again that schism is set in motion by technology that's uncomfortably organic in nature, implying that we're being slowly transformed by our relationship with technology in ways that we often neither anticipate nor fully understand. It's the New Flesh in the form of a multi-player video game. Even the organic gun that figures prominently in eXistenZ recalls Max Renn's fleshy "handgun" in Videodrome.

Recycled themes notwithstanding, eXistenZ serves as a neat summation of Cronenberg's preoccupations during his genre years. Additionally, it displays more of Cronenberg's skewed humor than we've seen in the past. While not Cronenberg's strongest effort, eXistenZ is still well worth a watch.

_________________________________________________________________________

While David Cronenberg continues to produce intelligent and compelling work -

A History Of Violence (2005), Eastern Promises (2007), A Dangerous Method (2011) - he's been absent from the horror genre in which he made his name for well over a decade now. That's a shame. Cronenberg always recognized the genre movie as an apt forum for discussion of subject matter that might otherwise be considered difficult or taboo, and we need more visionaries who recognize that potential.

Here's hoping he comes back to us some day.

Posted by Brandon Early